If there is one moment I’ll never forget, it was the little box hovering a few feet in the air. When my girlfriend walked in, she thought it was a clever piece of art, made to look as though held up by some wires hanging off the side. When I demonstrated that it really was just hovering there, she just walked out of the room saying “that’s cool.”

My total shock at her not realizing the implications of a little floating box is probably why I remember it so well; after all, who would believe I’d literally just invented propulsion-less flight in my tiny office? That moment led to the SkyFox v1. By now, most people are pretty familiar with the SkyFox and the DeepWolf, but very few people ever saw the first few iterations.

This first iteration of the SkyFox was literally a platform and some controls. The first few flights were done sitting on top of the platform, hoping it wouldn’t kill me. Not long after that, we did our first actual flight, under the radar, in an old flying VW bug, late at night, across the Atlantic. It was so cool to spend a day in France, with nobody the wiser.

That was a pivotal moment, having a glass of wine with my friends, discussing if we should find funding or not. We knew what we had: inexpensive, unlimited flight; as long as you had electricity, you could go anywhere in the known universe. We also knew, we were relatively poor college students.

It was David’s idea, honestly, that would lead to some world-changing events. His idea was simple, yet brilliant: let’s fly out to the asteroid belt, grab a few rare minerals, and bring them back. It quickly devolved into a discussion about how we would make it believable:

- We need a defunct mine that we can use to launch from.

- We need contracts.

- We need to know what kind of minerals we can get back to earth.

- We need to accidentally not kill everyone on Earth by causing an extinction-level event.

We flew home at the end of the weekend, lost in our own thoughts.

While David would usually be the one with the good ideas, it was always Isaac who executed them perfectly. A few weeks later, Isaac burst into my office (which was quickly becoming dubbed “the lab”) yelling some incoherent nonsense about how he “found it” and something else about Argentina. Because my memoirs suck (I highly recommend reading Isaac’s, which are much better put together), you can likely deduce that he found a defunct mine he thought we could afford.

Of course, you would also be correct. We decided to pull all our grant money into an “illegal” slush fund and “just do it man.” Thus began Area 92…

Area 92 is up in the mountains of Argentina, a bit off the beaten path, but perfect for us. We gave up our nice and easy life, convinced our parents, one way or another, that we were going off to an internship. For the next 8 months, we built SkyFox v2, an egg-shaped concrete ship that you’ve probably seen in plenty of documentaries, so I won’t go into it. It sucked. I hated that thing so much. It had so many problems, the most annoying one being the electrical system. If I remember correctly, it was a mouse or rat or something that got stuck between some concrete and lived for a few days or so, eating everything it could get its teeth into; especially the wiring.

Anyway, we eventually launched, late at night. It was a bit scary since piloting the craft worked via an experimental VR interface that had never actually been tested before. I remember watching the telemetry data in real time, while Dawn, our lead engineer and resident flight simulator expert, operated it from the inside, and into space. She survived, of course, but at the time, we didn’t know if she actually would. We had planned an entire plausible death for her if she didn’t make it back, but luckily, everything went according to plan. I can’t imagine doing that at this age, but back then, it seemed like a good idea.

Later that week, Dawn, Dan, and Isaac left for the belt. We kept any kind of radio emissions at zero, so we weren’t too worried about being picked up by astronomers. We did our best to keep to Earth’s shadow until we were beyond the orbit of the moon, speeding up at just over 1 g the whole time. Just to be clear, we kept gravity around 1.5 g at all times, except when parking beside asteroids. Even then, we sometimes accelerated at ~0.5-2.0 g to lock our position “above” rotating asteroids, but that was a bit later.

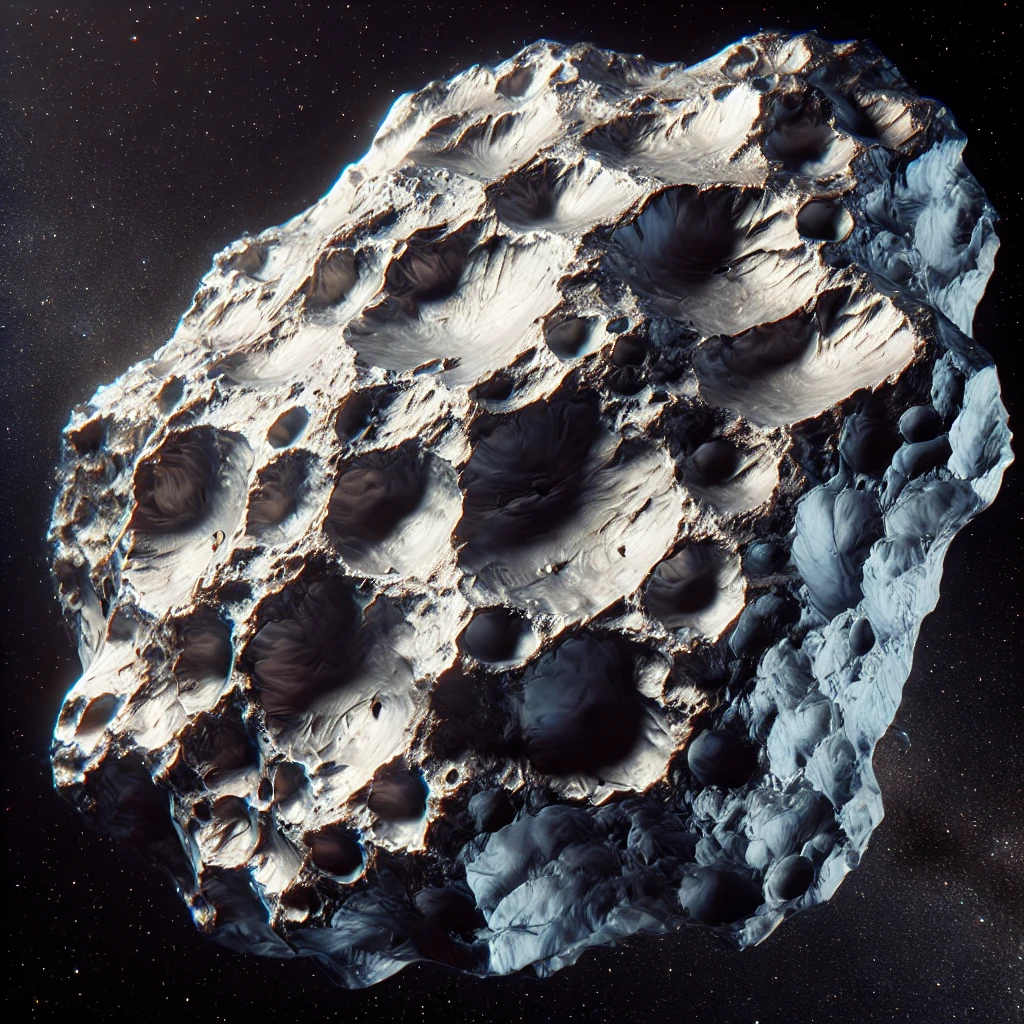

About a week later, they returned with various samples from asteroids and we went through them, analyzing what we had found. Eventually, we classified an asteroid (about 100 m in size) as “mostly platinum group metals” and did some math. We found that this asteroid was worth about 30 trillion dollars.

We celebrated that night. I have some fond memories of it, for sure…

Of course, we had to get the minerals back to earth and we had to sell it slowly, so as to not decrease the value of the minerals. We made some calls to some people and lined up some buyers. If we could pull it off, we were looking at over 100 billion dollars this first year. I remember there also being some worry that the sample we collected wasn’t representative, and the whole thing could be a dud.

Well, we made the deals and took out a huge loan to pull it off. We also had to bribe a few appraisers along the way if I recall correctly. We had to be sure that we “actually” had the minerals, but it did help that we had samples!

Within two months, we had SkyFox v2 outfitted for the journey and off we went. We all went this time. All of us. This was when I came to hate the design. It just wasn’t ergonomic. During most of the trip, I ended up working on what would become the most loved aspect of SkyFox: the 3-floor crew quarters and galley areas that are a trademark in our industry today.

Naturally, we spent nearly a week in the black trying to find the original asteroid we had mapped. It turns out that the orbits out there are not as straightforward as you might think!

Needless to say, we found it!

Fast forward a year later, and we built our first moon base. It was a rough spot, but this allowed us a great venue to refine some of our mining technology. Low gravity is perfect for this, while Earth gravity is just too strong. We eventually excavated enough to settle into what is now known as Earth Prime Station. By now, we were also hiring a few people to take care of day-to-day operations and our first “real” pilot, Jim. The employment contracts for these guys were insane. We had no idea what we were doing! Ha!

It was around this time that I became the actual CEO of the company, and we split everything nearly equally. I got the deciding 1% since it was my invention, but I didn’t care, at the time anyway. Well, ok. It kinda went to my head.

It was not long after that that we went public with everything and dared anyone to challenge us if they thought we didn’t own the minerals — yay space treaties! It was during one of the interviews that I mentioned if anyone sanctioned us, we would just drop an asteroid on them and … well, that began an exhilarating story.

See, a couple of governments thought they’d try to just “walk in and acquire the technology” since … well, reasons. Since Area 92 was relatively isolated, we saw them coming and just took off. Once we found out which government it was, well, we erased one of their mountains, and nobody bothered us again. Many people tried to get ahold of the technology, and we really didn’t want people to know that it worked (mostly) off of materials you could buy at a store. Everyone knows this, even today, but nobody knows what those things are.

We ended up building a couple of more moon bases, operating orbital flights, and built Emerald Station above Earth within five years of that. Within the next 10? We owned most of the solar system, and the rest is history.

That’s how we did it. It’s all David’s idea.

I highly recommend picking up Isaac’s Memoirs, he goes into great detail about his experiences in day-to-day operations and all the drama that surrounds it!